1.1.1 Basic Principles When Providing Care

- Where feasible, ensure that the woman has a companion of her choice with her.

- Provide information to the woman – and any accompanying family members the woman would like to be involved in decision-making – about diagnostic tests to be performed, supportive care to be provided (e.g. IV infusion), the process of care, her diagnosis, treatment options and the estimated time for in-patient care if required.

- If the woman is unconscious, explain the procedure to her family.

- Obtain informed consent for any procedures, diagnostic or therapeutic, and care.

1.1.2 Infection Prevention and Control

- In the context of maternal and newborn health care, infection prevention and control has three primary objectives:

- to prevent major infections when providing services;

- to minimize the risk of transmitting serious diseases such as hepatitis B and HIV/AIDS to the women and to health care providers and staff, including cleaning and housekeeping personnel; and

- to protect the environment by properly disposing of medical waste.

- The recommended infection prevention and control practices are based on the following principles:

- Consider every person (woman or staff) as potentially infectious.

- Handwashing is the most practical procedure for preventing cross-contamination.

- Wear gloves before touching anything wet – broken skin, mucous membranes, blood or other body fluids (secretions or excretions).

- Use barriers (e.g. protective goggles, face masks or aprons) if splashes and spills of any body fluids (secretions or excretions) are anticipated.

- Use safe work practices such as not recapping or bending needles, proper instrument processing, and proper disposal of medical waste.

Handwashing

- Thousands of people die every day around the world from infections

acquired while receiving health care. - Hands are the main pathways of germ transmission during health care.

- Hand hygiene is therefore the most important measure to avoid the transmission of harmful germs and prevent health care-associated infections.

- Clean your hands by rubbing them with an alcohol-based formulation,

as the preferred mean for routine hygienic hand antisepsis if hands are not visibly soiled. It is faster, more effective, and better tolerated by your hands than washing with soap and water. - Wash your hands with soap and water when hands are visibly dirty or visibly soiled with blood or other body fluids or after using the toilet.

- If exposure to potential spore-forming pathogens is strongly suspected or proven, including outbreaks of Clostridium difficile, hand washing with

soap and water is the preferred means.

- Clean your hands by rubbing them with an alcohol-based formulation,

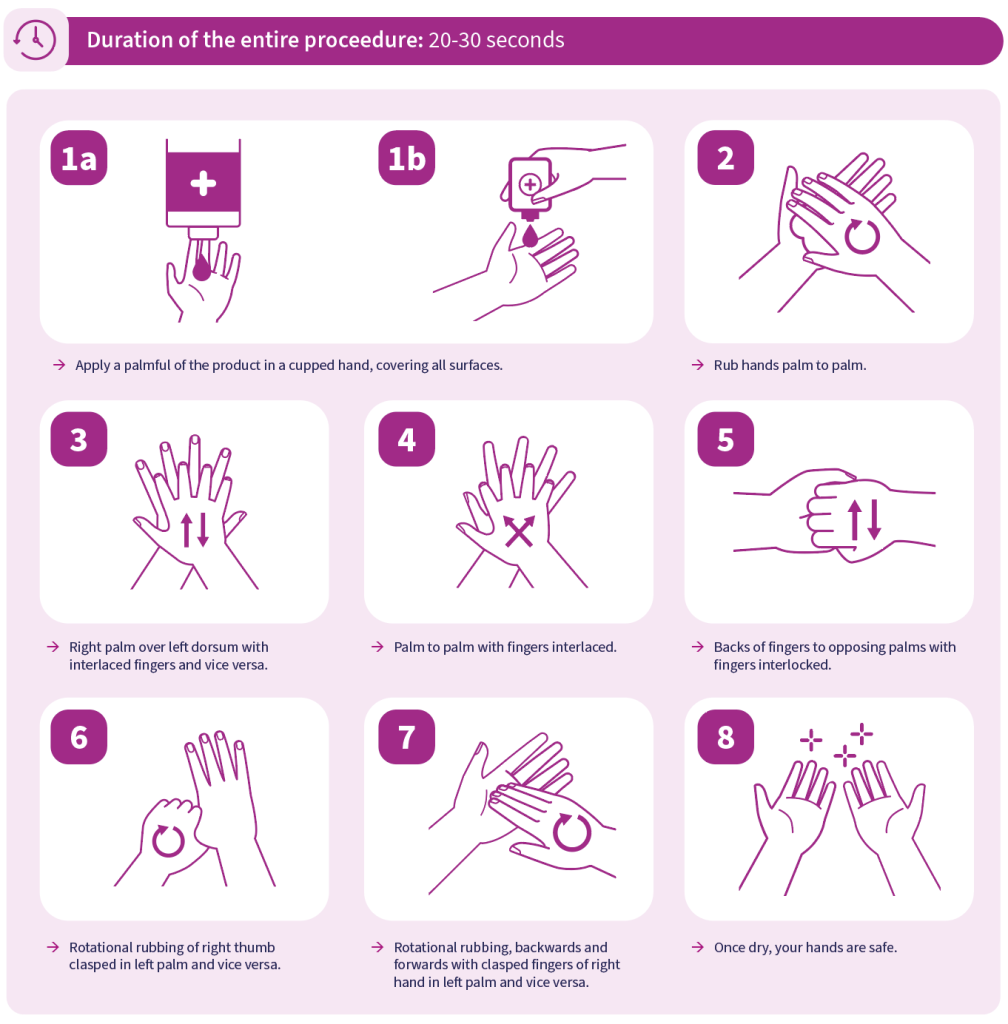

How to handrub with alcohol-based solution?

- If hands are not visibly dirty, use handrub with an alcohol-based solution for antimicrobial activity.

- Use plenty of handrub, enough to cover both hands, and rub all parts of the hands for 30 seconds or until hands are dry.

- Note:

- Remove rings, wrist watches and bracelets.

- Avoid wearing artificial nails because they increase the risk of hands remaining contaminated even after washing with soap and water and using alcohol-based handrub.

- Keep your natural nails short.

- Take care of your hands by regularly using a protective hand cream or lotion, at least daily.

- Do not routinely wash hands with soap and water immediately before or after using an alcohol-based handrub.

- Do not use hot water to rinse your hands.

- After handrubbing or handwashing, let your hands dry completely before putting on gloves.

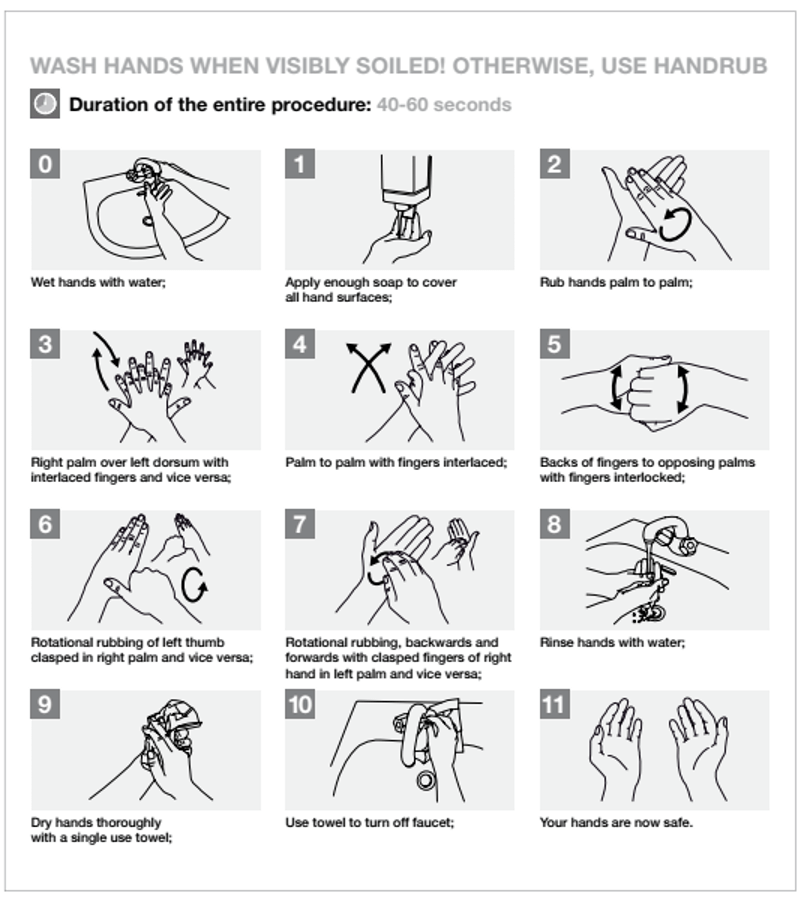

How to handwash with soap?

- Handwashing with water and soap removes visible dirt and organic material as well as bacterial contamination.

- Thoroughly rub together all surfaces of the hands lathered with plain or antimicrobial soap. Wash for 15–30 seconds and rinse with a stream of running or poured water.

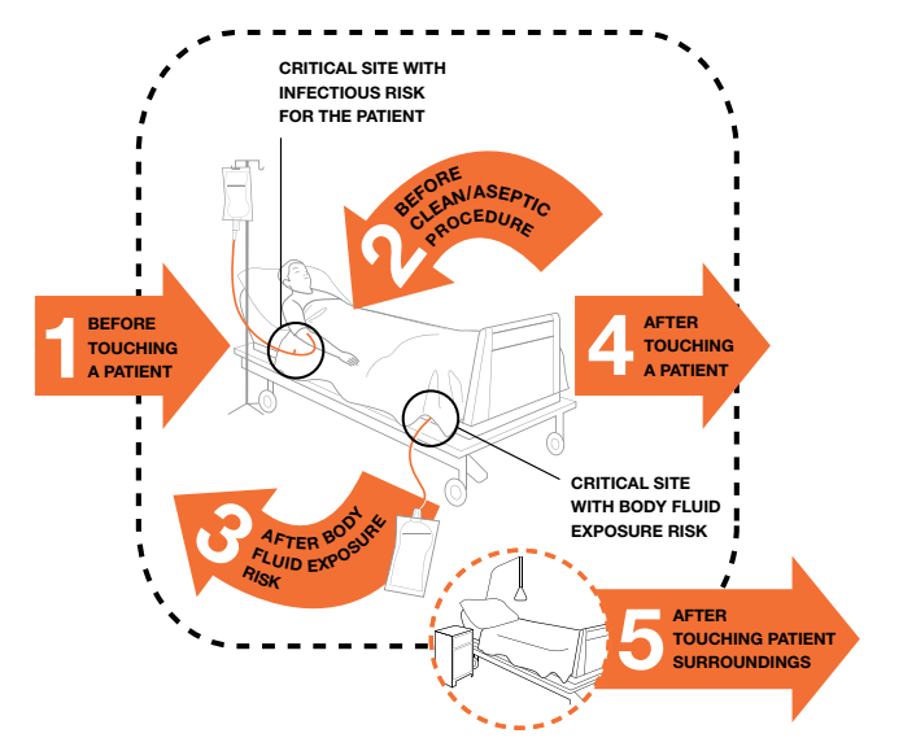

When to perform hand hygiene?

Moment 1: Before touching a patient

WHY? To protect the patient against colonization and, in some cases, against exogenous infection, by harmful germs carried on your hands.

WHEN? Clean your hands before touching a patient when approaching her.

Situations when Moment 1 applies:

- Before shaking hands, before stroking a child’s forehead

- Before assisting a patient in personal care activities: to move, to take a bath, to eat, to get dressed, etc

- Before delivering care and other non-invasive treatment: applying oxygen mask, giving a massage

- Before performing a physical non-invasive examination: taking pulse, blood pressure, chest auscultation, recording ECG.

Moment 2: Before clean / aseptic procedure

WHY? To protect the patient against infection with harmful germs, including his/her own germs, entering his/her body.

WHEN? Clean your hands immediately before accessing a critical site with infectious risk for the patient (e.g. a mucous membrane, non-intact skin, an invasive medical device).

Situations when Moment 2 applies:

- Before brushing the patient’s teeth, instilling eye drops, performing a digital vaginal or rectal examination, examining mouth, nose, ear with or without an instrument, inserting a suppository / pessary, suctioning mucous

- Before dressing a wound with or without instrument, applying ointment on vesicle, making a percutaneous injection / puncture

- Before inserting an invasive medical device (nasal cannula, nasogastric tube, endotracheal tube, urinary probe, percutaneous catheter, drainage), disrupting/opening any circuit of an invasive medical device (for food, medication, draining, suctioning, monitoring purposes)

- Before preparing food, medications, pharmaceutical products, sterile material

Moment 3: After body fluid exposure risk

WHY? To protect you from colonization or infection with patient’s harmful germs and to protect the health-care environment from germ spread.

WHEN? Clean your hands as soon as the task involving an exposure risk to body fluids has ended (and after glove removal)

Situations when Moment 3 applies:

- When the contact with a mucous membrane and with non-intact skin ends

- After a percutaneous injection or puncture; after inserting an invasive medical device (vascular access, catheter, tube, drain, etc); after disrupting and opening an invasive circuit

- After removing an invasive medical device

- After removing any form of material offering protection (napkin, dressing, gauze, sanitary towel, etc)

- After handling a sample containing organic matter, after clearing excreta and any other body fluid, after cleaning any contaminated surface and soiled material (soiled bed linen, dentures, instruments, urinal, bedpan, lavatories, etc)

Moment 4: After touching a patient

WHY? To protect you from colonization with patient germs and to protect the health-care environment from germ spread

WHEN? Clean your hands when leaving the patient’s side, after having touched the patient

Situations when Moment 4 applies, if they correspond to the last contact with the patient before leaving him / her:

- After shaking hands, stroking a child’s forehead

- After you have assisted the patient in personal care activities: to move, to bath, to eat, to dress, etc

- After delivering care and other non-invasive treatment: changing bed linen as the patient is in, applying oxygen mask, giving a massage

- After performing a physical non-invasive examination: taking pulse, blood pressure, chest auscultation, recording ECG

Moment 5: After touching patient surroundings

WHY? To protect you from colonization with patient germs that may be present on surfaces/ objects in patient surroundings and to protect the health-care environment against germ spread.

WHEN? Clean your hands after touching any object or furniture when leaving the patient surroundings, without having touched the patient

This Moment 5 applies in the following situations if they correspond to the last contact with the patient surroundings, without having touched the patient:

- After an activity involving physical contact with the patient’s immediate environment: changing bed linen with the patient out of the bed, holding a bed trail, clearing a bedside table

- After a care activity: adjusting perfusion speed, clearing a monitoring alarm

- After other contacts with surfaces or inanimate objects (note – ideally try to avoid these unnecessary activities): leaning against a bed, leaning against a night table / bedside table.

- To encourage handwashing, programme managers should make every effort to provide soap and a continuous supply of clean, potable water, from either the tap or a bucket, and single-use towels. Do not use shared towels to dry hands.

- To wash hands for surgical procedures, see section on operative care principles.

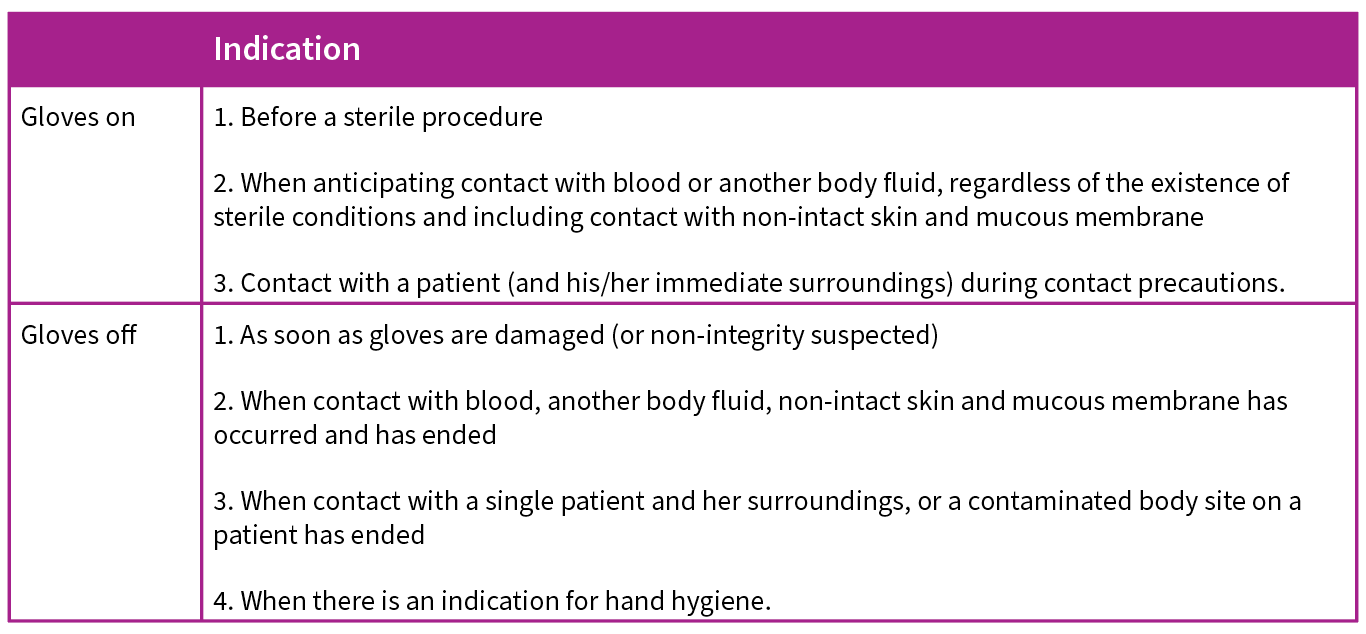

Hand hygiene and medical glove use

- The use of gloves does not replace the need for cleaning your hands.

- Hand hygiene must be performed when appropriate regardless of the indications for glove use.

- Remove gloves to perform hand hygiene, when an indication occurs while wearing gloves.

- Discard gloves after each task and clean your hands – gloves may carry germs.

- Wear gloves only when indicated according to Standard and Contact Precautions (see examples in the pyramid below) – otherwise they become a major risk for germ transmission.

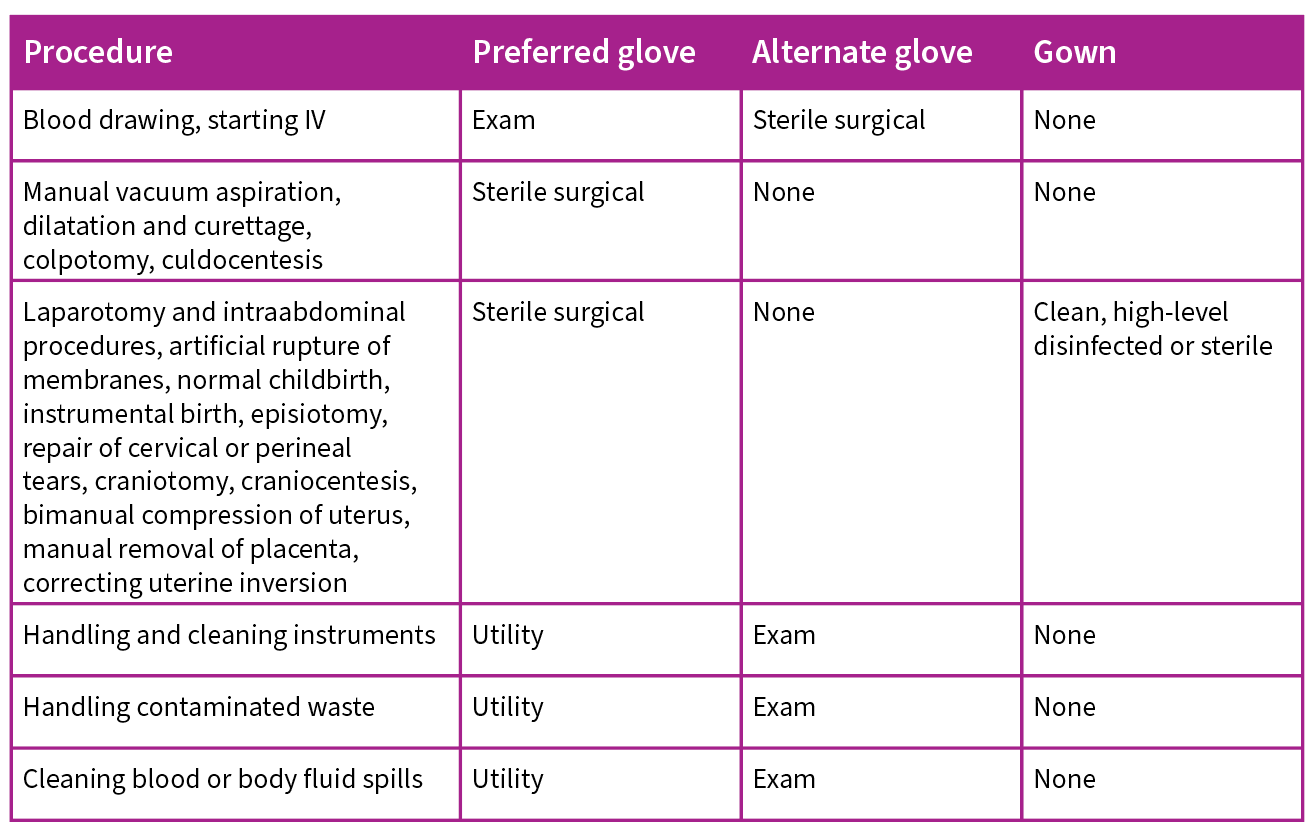

Gloves and gowns

- The use of gloves does not replace the need for hand hygiene by either handrubbing or handwashing.

- Medical gloves are defined as disposable gloves used during medical procedures; they include:

- Examination gloves (non-sterile or sterile)

- Surgical gloves that have specific characteristics of thickness, elasticity and strength and are sterile

- Medical gloves are recommended to be worn for two main reasons:

- To reduce the risk of contamination of health-care workers hands with blood and other body fluids.

- To reduce the risk of germ dissemination to the environment and of transmission from the health-care worker to the patient and vice versa, as well as from one patient to another.

- Gloves should therefore be used during all patient-care activities that may involve exposure to blood and all other body fluid (including contact with mucous membrane and non-intact skin), during contact precautions and outbreak situations.

- Wear gloves:

- when there is a chance of touching blood, body fluids, secretions or excretions;

- when performing a procedure (Table);

- when handling soiled instruments, gloves or other items soiled with body fluids; and

- when disposing of contaminated waste items (cotton, gauze or dressings).

Wash hands before retrieving gloves from a box to prevent introducing skin commensals and pathogenic bacteria into glove boxes.

Wash hands before retrieving gloves from a box to prevent introducing skin commensals and pathogenic bacteria into glove boxes.

- When wearing gloves, change or remove them when moving from a contaminated body site to another body site (including a mucous membrane, non-intact skin or medical device within the same woman or the environment).

- Change gloves between caring for different individuals. A separate pair of gloves must be used for each woman to avoid cross-contamination.

- Immediately remove gloves after completing a procedure or caring for a woman. Do not walk around with contaminated gloves as this will contaminate the environment. Do not wear the same pair of gloves for the care of more than one patient.

- Remove gloves by turning the first glove inside out as it is pulled over the hand. During the removal of the second glove, avoid touching the outer surface by slipping the fingers of the ungloved hand under the glove and pulling it inside out as it is pulled over the hand.

- Immediately dispose of the used gloves in a lined waste container. The reuse of gloves after reprocessing or decontamination is not recommended. Disposable gloves are preferred.

- Immediately clean hands with handrub or soap and water after removing gloves. Gloves do not provide complete protection against hand contamination. Pathogens may gain access to the caregivers’ hands via small defects in gloves or by contamination of the hands during glove removal. Hand hygiene by rubbing or washing remains the basic to guarantee hand decontamination after glove removal.

The Glove Pyramid – to aid decision making on when to wear (and not wear) gloves

Gloves must be worn according to STANDARD and CONTACT PRECAUTIONS. The pyramid details some clinical examples in which gloves are not indicated, and others in which examination or sterile gloves are indicated. Hand hygiene should be performed when appropriate regardless of indications for glove use.

- A clean, but not necessarily sterile, gown should be worn during all childbirth procedures:

- If the gown has long sleeves, the gloves should be put on over the gown sleeve to avoid contamination of the gloves.

- Ensure that gloved hands (sterile) are held above the level of the waist and do not come into contact with the gown.

- In addition to the gown, goggles and mask should be worn as a measure of protection.

Glove and gown requirements for common obstetric procedures

- Gloves and gowns are not required to be worn to check blood pressure or temperature, or to give injections.

- Alternative gloves are generally more expensive and require more preparation than preferred gloves.

- Exam gloves are single-use, disposable latex gloves.

- Surgical gloves are latex gloves that are sized to fit the hand.

- Utility gloves are thick household gloves.

Handling sharp instruments and needles

Operating theatre and labour ward

- Do not leave sharp instruments or needles (“sharps”) in places other than “safe zones”.

- Alert other workers before passing sharps.

Hypodermic needles and syringes

- Use each needle and syringe only once.

- Promptly dispose of needles and syringes in a puncture-proof container.

- Do not disassemble a needle and syringe after use.

- Do not recap, bend or break needles prior to disposal.

- Make hypodermic needles unusable by burning them.

Waste disposal

- The purpose of waste disposal is to:

- minimize the spread of infections and reduce the risk of accidental injury to staff, clients and visitors;

- protect those who handle waste from infection and accidental injury;

- prevent the spread of infection to the local community; and

- reduce the likelihood of contamination of the soil or ground water with chemicals or microorganisms.

- Health facilities generate four kinds of waste:

- noncontaminated waste,

- sharps,

- nonsharps contaminated waste and

- hazardous waste.

- Waste should be sorted, placed into separate waste containers and disposed of

appropriately:- Noncontaminated waste (e.g. paper from offices, boxes) poses no infectious risk and can be disposed of according to local guidelines.

- Proper handling of contaminated waste (blood- or body fluid–contaminated items) is required to minimize the spread of infection to hospital personnel and the community. Proper handling means:

- wearing utility gloves;

- transporting solid contaminated waste to the disposal site in covered containers;

- disposing of all sharp items in puncture-proof containers;

- carefully pouring liquid waste down a drain or flushable toilet (dedicated toilet that is not one used by clients or staff);

- burning or burying contaminated solid waste; and

- washing hands, utility gloves and containers after disposal of infectious waste.

1.1.3 Starting an IV Infusion

- Explain what is involved in giving an IV infusion and its purpose to the woman and any accompanying family members the woman would like to have involved in decision-making. If the woman is unconscious, explain the procedure to her family.

- Obtain informed consent for starting an IV infusion.

- Start an IV infusion (two if the woman is in shock) using a large-bore (16-gauge or largest available) cannula or needle.

- Infuse IV fluids (normal saline or Ringer’s lactate) at a rate appropriate for the woman’s condition.

- Note: If the woman is in shock, avoid using plasma substitutes (e.g. dextran). There is no evidence that plasma substitutes are superior to normal saline in the resuscitation of a woman in shock, and dextran can be harmful in large doses.

- If a peripheral vein cannot be cannulated, perform a venous cutdown.

1.1.4 Basic Principles for Procedures

Before any simple (non-operative) procedure, the following steps are necessary:

- Where feasible, ensure that the woman has a companion of her choice during the procedure.

- Gather and prepare all supplies. A lack of needed supplies can disrupt a procedure.

- Explain the procedure and the need for it to the woman and any accompanying family members the woman would like to have involved in decision-making. If the woman is unconscious, explain the procedure to her family.

- Obtain informed consent for the procedure.

- Estimate the length of time for the procedure and provide pain medication accordingly.

- Place the woman in a position appropriate for the procedure being performed. For example, when performing manual vacuum aspiration, use the lithotomy position; during cardiopulmonary resuscitation on a pregnant woman with a gestational age of 20 weeks or more, perform left lateral tilt.

- Clean hands with soap and water or alcohol handrub and put on gloves appropriate for the procedure.

- If the vagina and cervix need to be prepared with an antiseptic for the procedure (e.g. manual vacuum aspiration):

- Wash the woman’s lower abdomen and perineal area with soap and water, if necessary.

- Gently insert a sterile speculum or retractor(s) into the vagina.

- Apply antiseptic solution (e.g. iodophors, chlorhexidine) three times to the vagina and cervix using a sterile ring forceps and a cotton or gauze swab.

- If the skin needs to be prepared with an antiseptic for the procedure (e.g. for a caesarean birth):

- Wash the area with soap and water, if necessary.

- Apply antiseptic solution (e.g. iodophors, chlorhexidine) three times to the area using a sterile ring forceps and a cotton or gauze swab.

- If the swab is held with a gloved hand, do not contaminate the glove by touching unprepared skin.

- Begin at the centre of the area and work outward in a circular

motion away from the area. - At the edge of the sterile field, discard the swab.

- Never go back to the middle of the prepared area with the same swab. Keep your arms and elbows high and surgical dress away from the surgical field.

- If the procedure is conducted under local, paracervical or spinal anaesthesia, keep the woman informed about progress during the procedure.

- After the procedure, inform the woman and accompanying family members of the woman’s choice about:

- how the procedure went;

- complications linked to the procedure (e.g. reaction to anaesthesia, too much bleeding, accidental injury);

- any pertinent findings;

- side effects to expect;

- managing pain related to the procedure; and

- estimated length of stay in the facility after the procedure.

- Provide instructions on post-procedure care and follow-up, including danger signs that indicate that the woman should return immediately to the facility for care.

1.1.5 Clinical Use of Blood, Blood Products, and Replacement Fluids

Obstetric care sometimes requires blood transfusions. It is important to use blood, blood products and replacement fluids appropriately and to be aware of the principles designed to assist health workers in deciding when (and when not) to transfuse.

The appropriate use of blood products is defined as the transfusion of safe blood products to treat a condition leading to significant morbidity or mortality that cannot be prevented or managed effectively by other means.

Conditions that might require blood transfusion include:

- postpartum haemorrhage leading to shock;

- loss of a large volume of blood at operative birth; and

- severe anaemia, especially in later pregnancy or if accompanied by cardiac failure.

Note: For anaemia in early pregnancy, treat the cause of anaemia and provide haematinics.

District hospitals should be prepared for the urgent need for blood transfusion. It is mandatory for obstetric units to keep stored blood available, especially type O negative blood and fresh frozen plasma, as these can be lifesaving.

Unnecessary use of blood products

Used correctly, blood transfusions can save lives and improve health. Like any therapeutic intervention, however, transfusion can result in acute or delayed complications, and it carries the risk of transmission of infectious agents. It is also expensive and uses scarce resources.

Transfusion is often unnecessary for the following reasons:

- Conditions that might eventually require transfusion can often be prevented by early treatment or prevention programmes.

- Transfusions of whole blood, red cells or plasma are often given to prepare a woman quickly for planned surgery or to allow earlier discharge from the hospital. Other treatments, such as the infusion of IV fluids, are often cheaper, safer and equally effective.

- Unnecessary transfusion can:

- expose the woman to unnecessary risks; and

- cause a shortage of blood products for women in real need.

Risks of transfusion

Before prescribing blood or blood products for a woman, it is essential to consider the risks of transfusing against the risks of not transfusing.

Whole blood or red cell transfusion

- The transfusion of red blood cell products carries a risk of incompatible transfusion and serious haemolytic transfusion reactions.

- Blood products can transmit infectious agents – including HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis, malaria and Chagas disease – to the recipient.

- Any blood product can become bacterially contaminated and very dangerous if it is manufactured or stored incorrectly.

Plasma transfusion

- Plasma can transmit most of the infections present in whole blood.

- Plasma can also cause transfusion reactions.

- There are very few clear indications for plasma transfusion (e.g. coagulopathy) and the risks often outweigh any possible benefit.

Blood safety

- The risks associated with transfusion can be reduced by:

- effective blood donor selection, deferral and exclusion;

- screening for transfusion-transmissible infections in the blood donor population (e.g. HIV/AIDS and hepatitis);

- quality-assurance programmes;

- high-quality blood grouping, compatibility testing, component separation, and storage and transportation of blood products; and

- appropriate clinical use of blood and blood products.

Screening for infectious agents

- Every unit of donated blood should be screened for transfusion-transmissible infections using the most appropriate and effective tests, in accordance with both national policies and the prevalence of infectious agents in the potential blood donor population.

- All donated blood should be screened for the following:

- HIV-1 and HIV-2

- Hepatitis B surface antigen

- Treponema pallidum antibody (syphilis).

- Where possible, all donated blood should also be screened for:

- Hepatitis C;

- Chagas disease, in countries where the seroprevalence is significant;

- Malaria, in areas with high prevalence of malaria and in low prevalence countries when donors have travelled to malarial areas.

- No blood or blood product should be released for transfusion until all nationally required tests are shown to be negative.

- Perform compatibility tests on all blood components transfused, even if, in life-threatening emergencies, the tests are performed after the blood products have been issued.

Blood that has not been obtained from appropriately selected donors and that has not been screened for transfusion-transmissible infectious agents (e.g. HIV, hepatitis) in accordance with national requirements should not be issued for transfusion, other than in the most exceptional life-threatening situations.

Principles of clinical transfusion

The fundamental principle of appropriate use of blood or blood product is that transfusion is only one element of managing urgent care for women. When there is sudden rapid loss of blood due to haemorrhage, surgery or complications of childbirth, the most urgent need is usually the rapid replacement of the fluid lost from circulation.

Transfusion of red cells might also be vital to restoring the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

Minimize “wastage” of a woman’s blood (to reduce the need for transfusion) by:

- using replacement fluids for resuscitation;

- minimizing the blood taken for laboratory use;

- using the best anaesthetic and surgical techniques to minimize blood loss during surgery;

- salvaging and reinfusing surgical blood lost during procedures (autotransfusion), where appropriate.

Principles to remember

- Transfusion is only one element of managing a woman’s care.

- Decisions about prescribing a transfusion should be based on national guidelines on the clinical use of blood, taking the woman’s needs into account.

- Blood loss should be minimized to reduce a woman’s need for transfusion.

- A woman with acute blood loss should receive effective resuscitation (IV replacement fluids, oxygen, etc.) while the need for transfusion is being assessed.

- The woman’s haemoglobin value, although important, should not be the sole deciding factor in starting the transfusion. The decision to transfuse should be supported by the need to relieve clinical signs and symptoms and prevent significant morbidity and mortality.

- The clinician should be aware of the risks of transfusion-transmissible infection in blood products that are available.

- Transfusion should be prescribed only when the benefits to the woman are likely to outweigh the risks.

- A trained person should monitor the transfused woman and respond immediately if any adverse effects occur.

- The clinician should record the reason for transfusion and investigate any adverse effects.

Prescribing blood and blood products

Prescribing decisions should be based on national guidelines on the clinical use of blood, taking the woman’s needs into account.

- Before prescribing blood or blood products for a woman, keep in mind the following:

- expected improvement in the woman’s clinical condition;

- methods to minimize blood loss to reduce the woman’s need for transfusion;

- alternative treatments that could be given, including IV replacement fluids or oxygen, before making the decision to transfuse;

- specific clinical or laboratory indications for transfusion;

- risks of transmitting HIV, hepatitis, syphilis or other infectious agents through the blood products that are available;

- benefits of transfusion versus risk for the particular woman;

- other treatment options if blood is not available in time;

- the need for a trained person to monitor the woman and immediately respond if a transfusion reaction occurs.

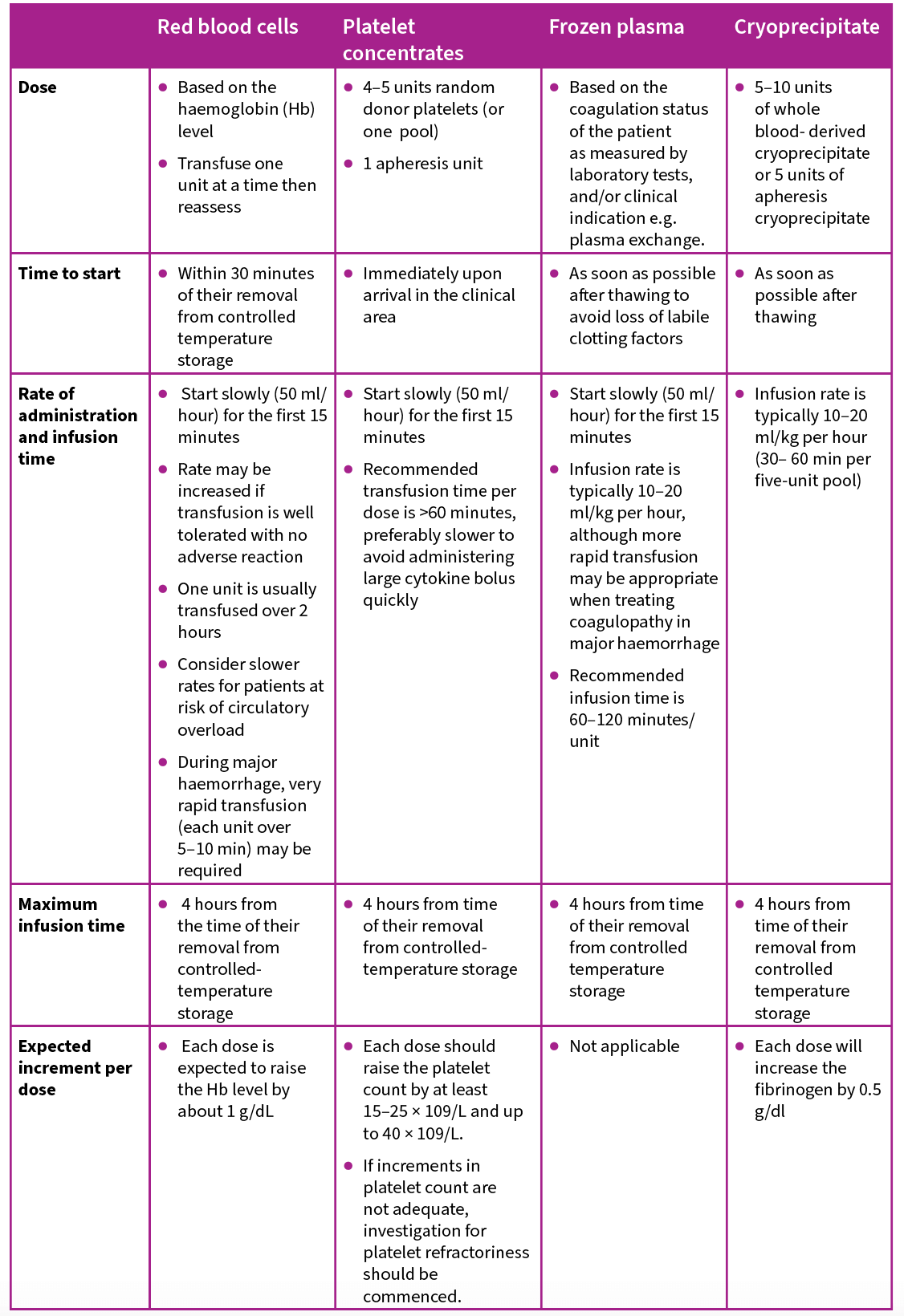

Dosage, time limit, rate of administration and expected outcomes for transfused blood products in an adult

Dosage, time limit, rate of administration and expected outcomes for transfused blood products in an adult

Monitoring the transfused woman

For each unit of blood transfused, monitor the woman at the following stages:

- before starting the transfusion;

- at the onset of the transfusion;

- 15 minutes after starting the transfusion;

- at least every hour during the transfusion;

- at four-hour intervals after completing the transfusion.

Closely monitor the woman during the first 15 minutes of the transfusion and regularly thereafter to detect early symptoms and signs of adverse effects.

At each of these stages, record the following information on the woman’s chart:

- general appearance

- temperature

- pulse

- blood pressure

- respiration

- fluid balance (oral and IV fluid intake, urinary output).

In addition, record:

- the time the transfusion is started;

- the time the transfusion is completed;

- the volume and type of all products transfused;

- the unique donation numbers of all products transfused; and

- any adverse effects.

Responding to a transfusion reaction

Transfusion reactions may range from a minor skin rash to anaphylactic shock. Stop the transfusion and keep the IV line open with IV fluids (normal saline or Ringer’s lactate) while making an initial assessment of the acute transfusion reaction and seeking advice.

If the reaction is minor, give promethazine 10 mg by mouth and observe.

Managing anaphylactic shock from mismatched blood transfusion

- Manage as for shock and give:

- adrenaline 1:1000 solution (0.1 mL in 10 mL normal saline or Ringer’s lactate) IV slowly;

- promethazine 10 mg IV; and

- hydrocortisone 1 g IV every two hours as needed.

- If bronchospasm occurs, give aminophylline 250 mg in 10 mL normal saline or Ringer’s lactate IV slowly.

- Continue resuscitation measures above until stabilized.

- Monitor renal, pulmonary and cardiovascular functions.

- Transfer to referral centre when stable.

Documenting a transfusion reaction

- Immediately after the reaction occurs, take the following samples and send with a request form to the blood bank for laboratory investigations:

- immediate post-transfusion blood samples:

- one clotted;

- one anticoagulated (EDTA/Sequestrene) taken from the vein opposite the infusion site;

- the blood unit and giving set containing red cell and plasma residues from the transfused donor blood;

- the first specimen of the woman’s urine following the reaction.

- immediate post-transfusion blood samples:

- If septic shock is suspected due to a contaminated blood unit, take a blood culture in a special blood culture bottle.

- Complete a transfusion reaction report form.

- After the initial investigation of the transfusion reaction, send the following to the blood bank for laboratory investigations:

- blood samples at 12 hours and 24 hours after the start of the

reaction:- one clotted;

- one anticoagulated (EDTA/Sequestrene) taken from the vein opposite the infusion site;

- all urine for at least 24 hours after the start of the reaction.

- Immediately report all acute transfusion reactions, with the exception of mild skin rashes, to a medical officer and to the blood bank that supplied the blood.

- Record the following information on the woman’s chart:

- type of transfusion reaction;

- length of time after the start of transfusion that the reaction occurred;

- volume and type of blood products transfused; and

- unique donation numbers of all products transfused.

- blood samples at 12 hours and 24 hours after the start of the

1.1.6 Replacement Fluids: Simple Substitutes for Transfusion

Only normal saline (sodium chloride 0.9%) or balanced salt solutions that have a similar concentration of sodium to plasma are effective replacement fluids. These should be available in all hospitals where IV replacement fluids are used.

Replacement fluids are used to replace abnormal losses of blood, plasma or other extracellular fluids by increasing the volume of the vascular compartment. They are used principally in:

- management of women with established hypovolaemia (e.g. haemorrhagic shock);

- maintenance of normovolaemia in women with on-going fluid losses (e.g. surgical blood loss).

Intravenous replacement therapy

Intravenous replacement fluids are the first-line treatment for hypovolaemia. Initial treatment with these fluids may be lifesaving and can provide some time to control bleeding and obtain blood for transfusion if it becomes necessary.

- Crystalloid replacement fluids

- contain a similar concentration of sodium to plasma;

- cannot enter cells because the cell membrane is impermeable to sodium; and

- pass from the vascular compartment to the extracellular space compartment (normally only a quarter of the volume of crystalloid infused remains in the vascular compartment).

- To restore circulating blood volume (intravascular volume), infuse crystalloids in a volume at least three times the volume lost.

Colloid fluids

- Colloid solutions are composed of a suspension of particles that are larger than crystalloids. Colloids tend to remain in the blood where they mimic plasma proteins to maintain or raise the colloid osmotic pressure of blood.

- Colloids are usually given in a volume equal to the blood volume lost.

- In many conditions where the capillary permeability is increased (e.g. trauma, sepsis), leakage out of the circulation will occur and additional infusions will be necessary to maintain blood volume.

Points to remember

- There is no evidence that colloid solutions (albumin, dextrans, gelatins, hydroxyethyl starch solutions) have advantages over normal saline or balanced salt solutions for resuscitation.

- There is evidence that colloid solutions may have an adverse effect on survival.

- Colloid solutions are much more expensive than normal saline and balanced salt solutions.

- Human plasma should not be used as a replacement fluid. All forms of plasma carry a risk, similar to that of whole blood, of transmitting infection, such as HIV and hepatitis.

Safety

Before giving any IV infusion:

- check that the seal of the infusion bottle or bag is not broken;

- check the expiry date;

- check that the solution is clear and free of visible particles.

Maintenance fluid therapy

Maintenance fluids are crystalloid solutions, such as dextrose or dextrose in normal saline, used to replace normal physiological losses through skin, lungs, faeces and urine. If it is anticipated that the woman will receive IV fluids for 48 hours or more, infuse a balanced electrolyte solution (e.g. potassium chloride 1.5 g in 1 L IV fluids) with dextrose.

The volume of maintenance fluids required by a woman will vary, particularly if the

woman has fever or if the ambient temperature or humidity is high, in which case losses will increase.

Other routes of fluid administration

There are other routes of fluid administration in addition to the IV route.

Oral and nasogastric administration

- This route can often be used for women who are mildly hypovolaemic and for women who can receive oral fluids.

- Oral and nasogastric administration should not be used if:

- the woman is severely hypovolaemic;

- the woman is unconscious;

- there are gastrointestinal lesions or reduced gut motility (e.g. obstruction);

- surgery with general anaesthesia is imminent.

Rectal administration

- Rectal administration of fluids is not suitable for severely hypovolaemic women.

- Advantages of rectal administration include the following:

- It allows the ready absorption of fluids.

- Absorption ceases and fluids are ejected when hydration is complete.

- It is administered through a plastic or rubber enema tube inserted into the rectum and connected to a bag or bottle of fluid.

- The fluid rate can be controlled by using an IV set, if necessary.

- The fluids do not have to be sterile. A safe and effective solution for rectal rehydration is 1 L of clean drinking water to which a teaspoon of table salt is added.

Subcutaneous administration

- Subcutaneous administration can occasionally be used when other routes of administration are unavailable, but this method is unsuitable for severely hypovolaemic women.

- Sterile fluids are administered through a cannula or needle inserted into the subcutaneous tissue (the abdominal wall is a preferred site).

- Solutions containing dextrose can cause tissue to die and should not be given subcutaneously.

1.1.7 Antibiotic Therapy

This chapter briefly discusses

- the use of prophylactic antibiotics before an obstetrical procedure,

- therapeutic use of antibiotics for suspected or established severe pelvic infection,

- management of antibiotic allergies, and

- antibiotic resistance.

Prophylactic antibiotics are given to help prevent infection.

If a woman is suspected to have or is diagnosed as having an infection, therapeutic antibiotics are indicated.

Recommendations for antibiotic treatment and prevention of specific conditions are discussed in the specific chapters. Infection during pregnancy and the postpartum period can be caused by a combination of organisms, including aerobic and anaerobic cocci and

bacilli. Antibiotics should be started based on specific indications, including:

- prevention of infection in the setting of established risk factors (e.g. vaginal colonization with Group B streptococcus);

- prophylaxis for medical procedures e.g. caesarean section or operative vaginal birth; and

- treatment of confirmed or suspected infection based on the clinical presentation of the woman.

Whenever possible, cultures and antibiotic sensitivities should be obtained (e.g. urine, vaginal discharge, pus) before initiating antibiotic treatment for a suspected infection so that treatment can be adjusted based on culture results or if there is no clinical response with treatment. However, prompt empiric treatment of severe infections based on clinical presentation should not be delayed if a facility does not have the capacity to collect or process cultures in a timely manner.

If bacteraemia (presence of bacteria in the blood) or septicaemia (presence and multiplication of bacteria in the blood) is suspected, a blood culture should be done whenever feasible.

Uterine infection can follow an abortion or childbirth and is a major cause of maternal death. Broad spectrum antibiotics often are required to treat these infections. In cases of unsafe abortion and non-institutional births, antitetanus prophylaxis should also be provided as part of comprehensive management.

Providing prophylactic antibiotics

Performing certain obstetric procedures (e.g. caesarean birth, manual removal of placenta) increases a woman’s risk of infectious morbidity. This risk can be reduced by:

- following recommended infection prevention and control practices; and

- providing prophylactic antibiotics at the time of the procedure.

Whenever possible, give prophylactic intravenous antibiotics 15–60 minutes before the start of a procedure to achieve adequate blood levels of the antibiotic at the time of the procedure. One dose of prophylactic antibiotics is sufficient and is no less effective than three doses or 24 hours of antibiotics for preventing infection after an obstetric procedure. If the procedure lasts longer than six hours or blood loss is 1500 mL or more, give a second dose of prophylactic antibiotics to maintain adequate blood levels during the procedure.

Obstetric procedures for which antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for the woman include the following:

- elective and emergency caesarean (note: prophylaxis to be given before starting the skin incision whenever possible);

- assisted vaginal birth;

- suturing of third and fourth degree genital tears;

- manual removal of the placenta; and

- placement of uterine balloon tamponade.

Providing therapeutic antibiotics

- For initial treatment of serious infections of the pelvic organs (e.g. uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries) or upper urinary tract, give a combination of broad spectrum antibiotics that target the most likely pathogen causing the infection.

- WHO’s AWARE guidelines provide recommendations for choice of antibiotics for specific infections and these are updated periodically.

- Specific antibiotic choices for infections during pregnancy, labour and postpartum period are given in the specific chapters in this tool.

- If the clinical response is poor after 48 hours, ensure that adequate dosages of antibiotics are being given and re-evaluate the woman for other sources of infection.

- Consider altering the treatment according to reported microbial sensitivity if cultures have been checked, and consider adding an additional agent to cover anaerobes if one was not included in the initial antibiotic combination.

- If culture facilities are not available, re-examine for pus collection, especially in the pelvis, and for non-infectious causes of pain and fever, such as deep vein and pelvic vein thrombosis.

- Consider the possibility of infection due to organisms resistant to the above combination of antibiotics and change antibiotics accordingly.

- If the infection does not clear, re-evaluate for the source of infection.

Allergies

Allergies can range from very mild skin rashes to life-threatening systemic anaphylactic reactions requiring immediate management to prevent death. Because of the potentially life-threatening risk of an allergic reaction to an antibiotic (or any medication), it is very important to rule out any previously known allergy to antibiotic or other medications before administering any medication.

If an antibiotic to which a woman has developed an allergy is needed for a significant infection for which no other options exist, then it is reasonable to decide whether or not to use the antibiotic based on the severity of the prior reported allergic reaction. In general, antibiotics that have been associated with a significant prior allergic reaction (e.g. anaphylaxis) should not be given unless under the close supervision of a trained physician. However, if the reported antibiotic allergic reaction was mild (e.g. rash) and did not involve systemic symptoms, or is not well documented (for e.g. a childhood memory of “reaction” to an antibiotic), then it is reasonable, if other options do not exist, to give a carefully supervised trial of the antibiotic.

Anaphylaxis

Anaphylaxis is a severe systemic allergic reaction that depends on rapid and timely management. Symptoms of anaphylaxis can include:

- a sense of tingling

- flushing

- swelling of the face, lips and tongue

- difficulty breathing due to swelling of the throat and airway

- shortness of breath

- abdominal cramps

- palpitations

- syncope

- Administer adrenaline 0.3–0.5 mg IM immediately, and repeat every 10 to 15 minutes, as needed.

- Monitor vital signs (blood pressure, pulse, respiration rate, oxygen saturation) and admit for observation.

- Try to identify the cause of the anaphylactic reaction (e.g. specific medication, food) and immediately discontinue the triggering factor.

- After an anaphylactic reaction, a woman should be monitored closely for at least 24–48 hours because there is a risk of a second rebound reaction. Rebound (biphasic) reactions almost always occur within the first 72 hours after an anaphylactic event. Consider beginning prednisolone 40–60 mg by mouth for three days to reduce the severity of a possible rebound reaction.

- Record the drug allergy in the woman’s case notes, and counsel her to:

- write down the name of the medication;

- inform all future providers that she has an allergy to this medication; and

- always avoid this medication in the future.

Mild allergic reactions

Mild allergic reactions usually involve itching and swelling and other cutaneous manifestations such as a new rash.

- Give antihistamines (e.g. loratadine 10 mg by mouth once daily) for mild cases.

- For more severe cases, add prednisolone 40–60 mg by mouth per day for five to seven days. If prednisolone is needed for longer than seven days to control symptoms, then taper down the prednisolone gradually over several days while observing symptoms (e.g. 30, 20, 10 and 5 mg).

Antimicrobial resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threatens the effective prevention and treatment of an ever-increasing range of infections caused by bacteria, parasites, viruses and fungi.

AMR occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change over time and no longer respond to medicines making infections harder to treat and increasing the risk of disease spread, severe illness and death. As a result, the medicines become ineffective and infections persist in the body, increasing the risk of spread to others.

AMR is a natural process that happens over time through genetic changes in pathogens. Its emergence and spread are accelerated by human activity, mainly the misuse and overuse of antimicrobials to treat, prevent or control infections in humans, animals and plants.

WHO has several initiatives to address the growing problem of AMR. One of them targeted at heath care providers is antimicrobial stewardship.

Antimicrobial stewardship is a systematic approach to educate and support health care professionals to follow evidence-based guidelines for prescribing and administering antimicrobials. To improve access to appropriate treatment and reduce inappropriate use of antibiotics, WHO developed the AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) classification of antibiotics. The WHO AWaRe antibiotic book provides concise, evidence-based guidance on the choice of antibiotic, dose, route of administration, and duration of treatment for more than 30 of the most common clinical infections in children and adults in both primary health care and hospital settings.

1.1.8 Anaesthesia and Analgesia

Pain relief may be required during labour and is required during and after operative procedures. Analgesic drugs and methods of support during labour, local anaesthesia, general principles for using anaesthesia and analgesia, and postoperative analgesia are discussed here.

Analgesic drugs during labour

- The perception of pain during labour depends greatly on a woman’s emotional state. Supportive care during labour provides reassurance and decreases the perception of pain.

- If a woman is distressed by pain, Offer both non-pharmacolgical and pharmacological options for pain relief.

- Encourage her to walk around or assume any comfortable position. Encourage her companion to massage her back or sponge her face between contractions and place a cool cloth at the back of her neck. Encourage the use of relaxation techniques including progressive muscle relaxation, breathing, music, mindfulness and other techniques. Allow the woman to take a warm bath or shower if she chooses. For most women, this is enough to cope with the pain of labour.

- Parenteral opioids, such as fentanyl, diamorphine and pethidine, are recommended options for healthy pregnant women requesting pain relief during labour, depending on a woman’s preferences. One option is to offer the woman:

- morphine 0.1 mg/kg body weight IM every four hours as needed, informing her of the advantages and disadvantages (see below) and obtaining consent;

- promethazine 25 mg IM or IV if vomiting occurs.

- If facilities are available for providing and monitoring epidural analgesia, offer this to the woman for pain relief.

Danger

If morphine is given to the woman within four hours before she gives birth, the baby may suffer from respiratory depression. Naloxone is the antidote.

Note: Do not administer naloxone to newborns whose mothers are suspected of having recently abused narcotic drugs. Naloxone is ONLY administered to a neonate with respiratory depression when opioids have been administered to the mother for pain relief during labour.

- If there are signs of respiratory depression in the newborn, begin resuscitation immediately:

- After vital signs have been established, give naloxone 0.1 mg/kg body weight IV to the newborn.

- If the infant has adequate peripheral circulation after successful resuscitation, naloxone can be given IM. Repeated doses may be required to prevent recurrent respiratory depression.

- If there are no signs of respiratory depression in the newborn, but morphine was given within four hours before birth, observe the baby for signs of respiratory depression and treat as above if they occur.

Premedication with promethazine and diazepam

Premedication is required for procedures that last longer than 30 minutes, for e.g. caesarean section, laparotomy. The dose must be adjusted to the weight and condition of the woman and to the condition of the fetus (when present). Inform the woman of the advantages and disadvantages and obtain consent.

- Offer morphine 0.1 mg/kg body weight IM, informing the woman of the advantages and disadvantages and obtaining consent.

- Give diazepam in increments of 1 mg IV and wait at least two minutes before giving another increment. A safe and sufficient level of sedation has been achieved when the woman’s upper eyelid droops and just covers the edge of the pupil.

- Monitor the respiratory rate every minute. If the respiratory rate falls below 10 breaths per minute, stop administration of all sedative or analgesic drugs.

- Monitor the fetal heart rate at least every 15 minutes. If the fetal heart rate falls below 100 beats per minute, stop administration of all sedative or analgesic drugs.

Local anaesthesia

Local anaesthesia (lidocaine with or without adrenaline) is used to infiltrate tissue and block the sensory nerves.

- Because a woman under local anaesthesia remains awake and alert during the procedure, it is especially important to ensure:

- counselling to increase cooperation and minimize her fears;

- good communication throughout the procedure as well as physical reassurance from the provider, if necessary;

- time and patience, as local anaesthetics do not take effect immediately;

- Awareness of the level of analgesia throughout the procedure to ensure the local anaesthesia continues to remain effective.

The following conditions are required for the safe use of local anaesthesia:

- All members of the operating team must be knowledgeable and experienced in the use of local anaesthetics.

- Emergency drugs and equipment (suction, oxygen, resuscitation equipment) should be readily available and in usable condition, and all members of the operating team trained in their use.

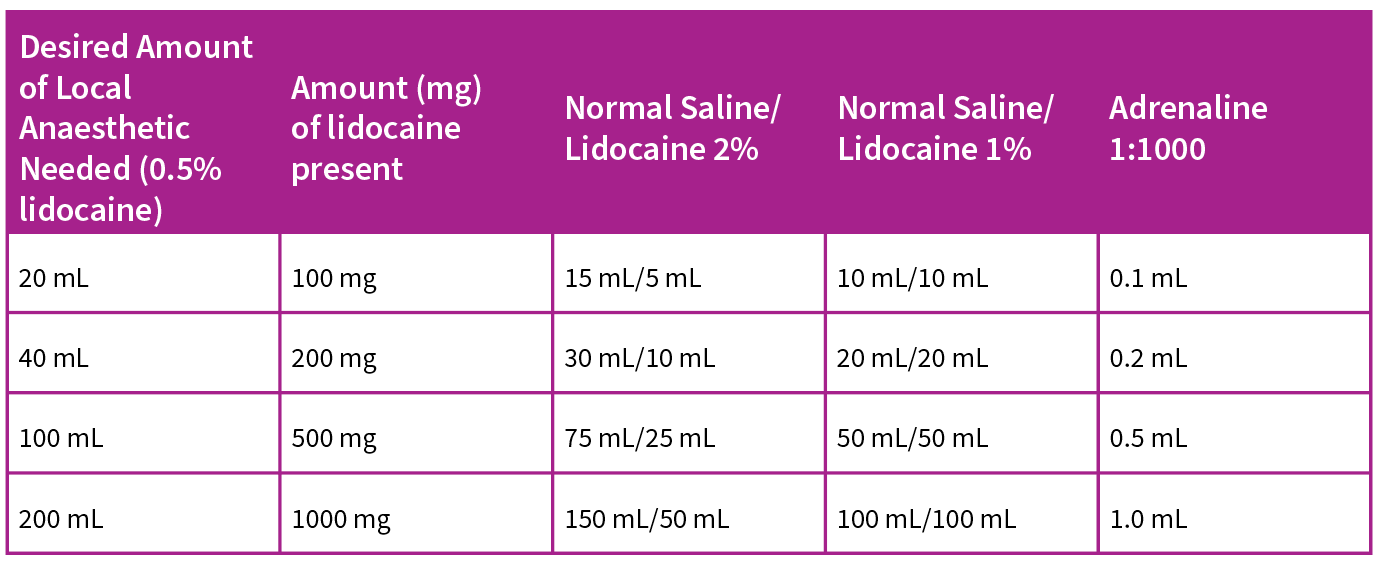

1.1.9 Lidocaine

Lidocaine preparations are usually 2% (20 mg/ml) or 1% (10 mg/ml) and require dilution before use (Box). For most obstetric procedures, the preparation is diluted to 0.5% (5 mg/ml), which gives the maximum effect with the least toxicity.

Preparation of lidocaine 0.5% solution

Combine:

- lidocaine 2%, one part; and

- normal saline or sterile distilled water, three parts (do not use glucose solution as it increases the risk of infection).

Or combine:

- lidocaine 1%, one part; and

- normal saline or sterile distilled water, one part.

Adrenaline

Adrenaline causes local vasoconstriction. Its use with lidocaine has the following advantages:

- less blood loss;

- longer effect of anaesthetic (usually one to two hours); and

- less risk of toxicity because of slower absorption into the general circulation.

If the procedure requires a small surface to be anaesthetized or requires less than 40 mL of lidocaine (equal to 200 mg of lidocaine if using 0.5% solution), adrenaline is not necessary. For larger surfaces, however, especially when more than 40 mL is needed, adrenaline is required to reduce the absorption rate and thereby reduce toxicity.

The best concentration of adrenaline is 1:200 000 (5 mcg/mL). This gives a maximum local effect with the least risk of toxicity from the adrenaline itself (Table).

Note: It is critical to measure adrenaline carefully and accurately using a syringe such as a bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) or insulin syringe. Mixtures must be prepared observing strict infection prevention practices.

TABLE: Formulas for preparing 0.5% lidocaine solutions containing 1:200 000 adrenaline

Complications

Prevention of complications

All local anaesthetic drugs are potentially toxic. Major complications from local anaesthesia, however, are extremely rare.

The best way to avoid complications is to prevent them:

- Avoid using concentrations of lidocaine stronger than 0.5%.

- If more than 40 mL of the anaesthetic solution is to be used (200 mg of lidocaine when using 0.5% solution), add adrenaline to delay dispersion. Procedures that might require more than 40 mL of 0.5% lidocaine are caesarean and repair of extensive perineal tears. Use cautiously because of the potential for toxicity at higher doses.

- Use the lowest effective dose.

- Observe the maximum safe dose (Table). For an adult, this is 4 mg/kg body weight of lidocaine without adrenaline and 7 mg/kg body weight of lidocaine with adrenaline. The anaesthetic effect should last for at least two hours. Doses can be repeated if needed after two hours.

- Inject slowly.

- Avoid accidental injection into a vessel. There are three ways of doing this:

- Moving needle technique (preferred for tissue infiltration): The needle is constantly in motion while injecting; this makes it impossible for a substantial amount of solution to enter a vessel.

- Plunger withdrawal technique (preferred for nerve block when considerable amounts are injected into one site): The syringe plunger is withdrawn before injecting; if blood appears, the needle is repositioned and attempted again.

- Syringe withdrawal technique: The needle is inserted and the anaesthetic is injected as the syringe is being withdrawn.

TABLE: Maximum safe doses of local anaesthetic drugs

| Drug | Maximum Dose (mg/kg of body weight) | Maximum Dose for 60 kg Adult |

| Lidocaine | 4 | 240 mg (48 ml of 0.5% solution) |

| Lidocaine + adrenaline 1:200 000 (5 mcg/mL) | 7 | 420 mg (84 ml of 0.5% solution) |

To avoid lidocaine toxicity:

- Use a dilute solution.

- Add adrenaline when more than 40 mL (200 mg) will be used.

- Use the lowest effective dose.

- Observe the maximum dose.

- Avoid IV injection.

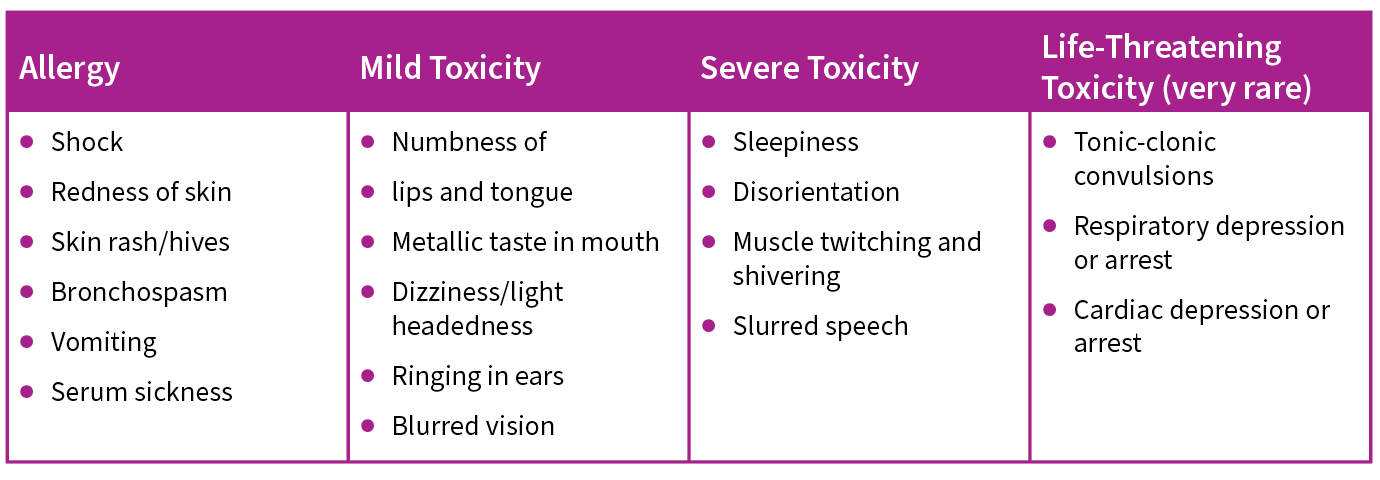

Diagnosis of Lidocaine allergy and toxicity

TABLE: Symptoms and signs of lidocaine allergy and toxicity

Management of Lidocaine allergy

- Give adrenaline 1:1000, 0.5 mL IM, and repeat every 10 minutes if necessary.

- In acute situations, give hydrocortisone 100 mg IV every hour.

- To prevent recurrence, give diphenhydramine 50 mg IM or IV slowly, then 50 mg by mouth every six hours.

- Treat bronchospasm with aminophylline 250 mg in normal saline 10 mL IV slowly.

- Laryngeal oedema may require immediate tracheostomy.

- For shock, begin standard shock management.

- Severe or recurrent signs may require corticosteroids (e.g. hydrocortisone IV 2 mg/kg body weight every four hours until condition improves). In chronic situations give prednisone 5 mg or prednisolone 10 mg by mouth every six hours until the condition improves.

Management of Lidocaine toxicity

Symptoms and signs of toxicity should alert the practitioner to immediately stop injecting and prepare to treat severe and life-threatening side effects. If symptoms and signs of mild toxicity are observed, wait a few minutes to see if the symptoms subside, check vital

signs, talk to the woman and then continue the procedure, if possible.

Convulsions

- Turn the woman to her left side, insert an airway and aspirate secretions.

- Give oxygen at 6–8 L per minute by mask or nasal cannulae.

- Give diazepam 1–5 mg IV in 1-mg increments. Repeat if convulsions recur.

- Note: The use of diazepam to treat convulsions may cause respiratory

Respiratory arrest

- If the woman is not breathing, assist ventilation using an Ambu bag and mask or via endotracheal tube; give oxygen at 4–6 L per minute.

Cardiac arrest

- Hyperventilate with oxygen.

- Perform cardiac massage.

- If the woman has not yet given birth, immediately perform a caesarean using general anaesthesia.

- Give adrenaline 1:10 000, 0.5 mL IV.

Adrenaline toxicity

- Systemic adrenaline toxicity results from inadvertent or excessive amounts of IV administration and results in:

- Restlessness

- Sweating

- Hypertension

- cerebral haemorrhage

- rapid heart rate

- ventricular fibrillation.

- Local adrenaline toxicity occurs when the concentration is excessive, and results in ischaemia at the infiltration site with poor healing.

General principles for anaesthesia and analgesia

- The keys to pain management and comfort are:

- supportive attention from staff before, during and after a procedure (helps reduce anxiety and lessen pain);

- a provider who is comfortable working with women who are awake and who is trained to use instruments gently; and

- the selection of an appropriate type and level of pain medication.

Tips for performing procedures on women who are awake include the following:

- Explain each step of the procedure before performing it.

- Use adequate premedication in cases expected to last longer than 30 minutes.

- Give analgesics or sedatives at an appropriate time before the procedure (30 minutes before for IM and 60 minutes before for oral medication) so that maximum relief will be provided during the procedure.

- Use dilute solutions in adequate amounts.

- Check the level of anaesthesia by pinching the area with forceps. If the woman feels the pinch, wait two minutes and then retest.

- Wait a few seconds after performing each step or task to allow the woman to prepare for the next one.

- Move slowly, without jerky or quick motions.

- Handle tissue gently and avoid undue retraction, pulling or pressure. During caesarean section, explain to the woman that she may feel pressure when the baby is being delivered, but that she will not feel pain.

- Use instruments with confidence.

- Avoid saying things like “this won’t hurt” if, in fact, it will hurt or “I’m almost finished” if you are not almost finished.

- Talk with the woman throughout the procedure.

- The need for supplemental analgesic or sedative medications (by mouth, IM or IV) depends on:

- the emotional state of the woman;

- the procedure to be performed;

- the anticipated length of the procedure; and – the skill of the provider and the assistance of the staff.

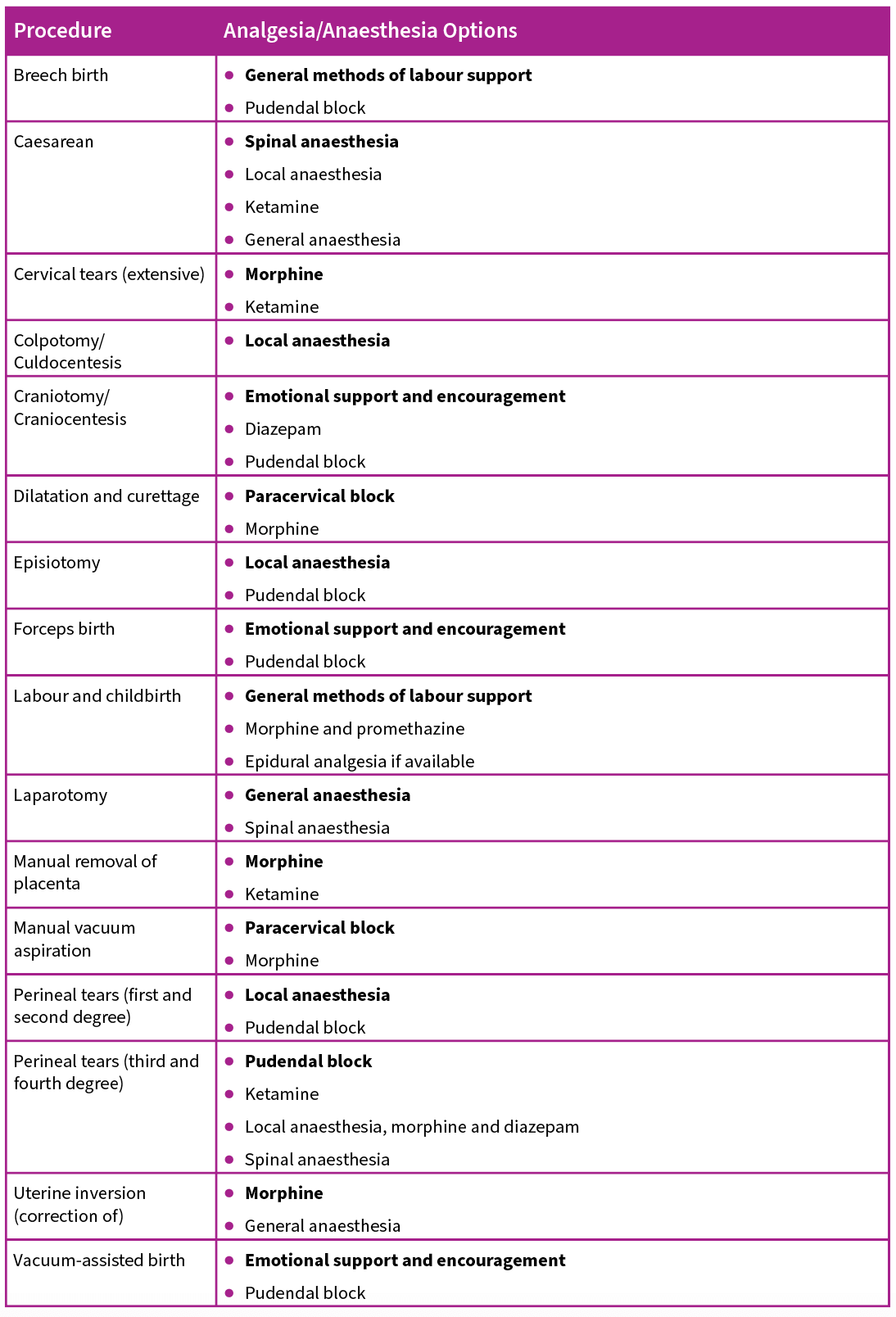

TABLE: Analgesia and anaesthesia options (The preferred analgesia/anaesthesia option is listed in bold.)

Postoperative analgesia

Adequate postoperative pain control is important. A woman who is in severe pain does not recover well.

Note: Avoid over-sedation as this will limit mobility, which is important during the postoperative period.

Good postoperative pain control regimens include:

- non-narcotic mild analgesics, such as paracetamol 500 mg by mouth as needed;

- narcotics such as morphine 0.1 mg/kg body weight IM every four hours as needed, informing the woman of the advantages and disadvantages and obtaining consent;

- combinations of lower doses of narcotics with paracetamol. Note: codeine is often combined with paracetamol and is contraindicated when breastfeeding.

- Note: If the woman is vomiting, narcotics may be combined with anti-emetics such as promethazine 25 mg IM or IV every four hours.

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.